Mr Henderson’s Railway -3

The road winds gently along the bottom of the valley, roughly keeping alongside the river and the railway line, but we are coming into the mountains. In Spain there are so many mountain ranges. They leap up all around you. Ahead we have to navigate around the foothills, and try to follow the river and Mr Henderson. It’s proving difficult.

We drive through Los Angeles. Across the valley is Jimena, another white town, set on a hillside, facing south-east. The main street is quite steep, as in so many of these white towns of Cadiz. And again, like so many of these little towns, the high street is all. Turn off into a side street and the pot holes lurk to catch you unawares, the pavement disappears, and the view leads down a steep incline, across the valley bottom, and up to the rolling foothills of the sierra.

Everywhere the fields are full of cattle. This is a rich agricultural region. Where the land is flat are fields of low rise cotton, the small white fluff blowing in the wind. A lorry roars along in front of us. There is no tarpaulin over its load, and parasols of cotton fly out from the back and scuttle across the road in front of us.

We pass through the village of San Pablo. But just before the village is a rather fine restaurant, with an interesting menu. We sit under the awning, and while away a pleasant hour or two, swapping notes with the folks next door who are eating dishes that I have not come across before. Rabo de Toro (bull’s tail) I have eaten many times before, but not cooked in this strange black sauce. It looks rather good. Then there is something that looks like a soggy milk pudding, but is a kind of pesto, which I have eaten up in the mountains at Tragacete at the source of the River Tajo (or Tagus). However, once again, this version is totally different, as it has been puréed.

On my second trip through here we stop again. It is a weekday and instead of day-trippers up from the coast there are delivery men, and locals, plus the occasional tourist. We have four large tapas, a pudding, a coffee, an orange juice, and two glasses of rioja; the bill is eleven euros.

The road is really starting to twist and turn as we approach Gaucin. This is a long straggling village, and it is where we briefly hit the railway again. The station is well to the west of the main village. It is very picturesque. Everywhere is green. There are trees, small fields, brightly coloured flowering trees and bushes tumble over outbuildings, with long fronds of pink and red.

As I wander among the rail tracks there is a blast from somewhere down the line, and a few moments later a long white train appears from out of the trees, and rattles past us, and disappears around another bend, further into the mountains towards Ronda.

We head up the wrong road, going the long way round to Cortes de la Frontera. The road almost immediately goes over a cattle grid into an ancient forest, which, according to the inscriptions on the tourist wall maps outside Gaucin station, is part of the last great rain forest of Europe. How far back this was all rain forest the text doesn’t say.

I quote: “there are many protected nature reserves… Los Alcomocales, the last Mediterranean rain forest; La Sierra de las Nieves, home of the Spanish fir….” (This fir seems to have a much longer leaf structure than the usual fir tree) “…and La Sierra de Grazalema, with a striking landscape caused by the exceptional rainfall; it receives more rain than any other region of the country.”

Well, that’s what it says, but somehow I find it hard to believe that this area receives more rainfall than the coastal regions of Galicia, and the mountainous area of Asturias.

The main tree is the cork oak, and there are great stacks of cork drying in a field. Then we are onto a twisting road that pushes its way through the trees with their orange-brown trunks, naked up to the first branches, which are themselves still clothed in the deeply rutted cork bark.

The trunks are stripped of the bark about every nine or ten years. In Portugal the trunks are numbered. Here no-one bothers. I have in fact wondered about the numbers in Portugal. Surely over the years they are covered by the new growth of bark, so that when the essential time for stripping it off again comes around they are not visible.

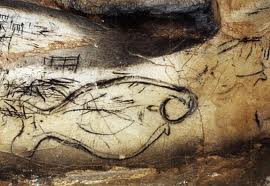

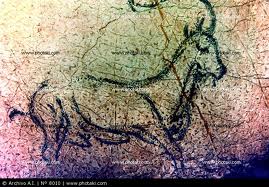

Back down in the valley are the caves with prehistoric paintings, but we’ll reach them next week.

john